Questioning Tariffs: What are the Motives Behind Trade Taxes

Understanding tariffs and how they have been used

Tariffs aren’t supposed to be part of modern trade policy. For decades, both parties embraced free trade and warned that tariffs hurt consumers. So when Donald Trump pushes them and says other countries are “ripping us off,” it sounds like a throwback, or a threat. But the real issue isn’t that he supports tariffs. It’s that he is unclear as to why, and his administration has offered numerous conflicting justifications. His critics aren’t much better; they quote Smith and Ricardo but skip over the most important question: What are the tariffs supposed to accomplish? Tariffs are taxes, with all the good or bad that entails. To judge them, you need to know the goal and whether the costs are worth the expected benefits.

Introduction: The Debate We’re Not Having

Tariffs spark instant reactions, some hail them as job-saving policies, others denounce them as taxes on consumers. Pundits bicker, economists publish charts, and the public is left trying to make sense of whether a price hike at the store is part of something smart or something stupid.

What’s usually missing from the noise is a simple question: What is this tariff supposed to accomplish?

Most debates skip that entirely. Instead, we jump straight to the effects—higher costs, lost efficiency, trade wars—without ever asking about the goal. But that’s like judging a note without knowing what song is being played. Is the tariff meant to protect an industry? Punish a competitor? Raise money? Change political policy? Until we understand that, we can’t meaningfully evaluate whether the policy makes any sense.

This article won’t settle the trade debate. But it will give you some background, a framework of ideas, for recognizing what’s really being said when the next tariff fight erupts. Because once you start asking what’s the point, the rest of the argument looks very different.

What Are Tariffs, Really?

At their core, tariffs are just taxes on goods that cross a border. A government sets a price—either as a percentage of the item’s value (ad valorem) or as a fixed fee per unit (specific tariff)—and collects that money from importers. That cost usually gets passed along to consumers. A $10 fee on a ton of steel and a 25% charge on foreign cars are the same idea, but with different applications.

But tariffs are more than just taxes. They’re tools of policy. Ways for governments to shape the flow of goods, protect domestic industries, or signal disapproval. That’s where things get more complicated.

Economists classify tariffs by their structure, economic effects, or the theoretical models that describe them. In those models, tariffs cause distortions. They raise prices, reduce efficiency, and create what economists call “deadweight loss”, a polite way of saying the economy works worse. As a rule, economists are skeptical that tariffs work well. Even when they serve a clear purpose, the costs are assumed to outweigh the benefits.

But here’s the catch: economic models depend on clearly defined goals. Without knowing why a tariff is being proposed, the predictions don’t tell us much. The math might show how prices or trade volumes could shift, but it can’t judge whether those changes are desirable. That depends on context, intent, and trade-offs. And in politics, those are rarely clear.

For policymakers and ordinary citizens alike, the intent is easier to grasp than calculating the outcome. You don’t need an economics degree to ask whether a policy is meant to punish a trade partner, protect a struggling factory, or push back against environmental abuses.

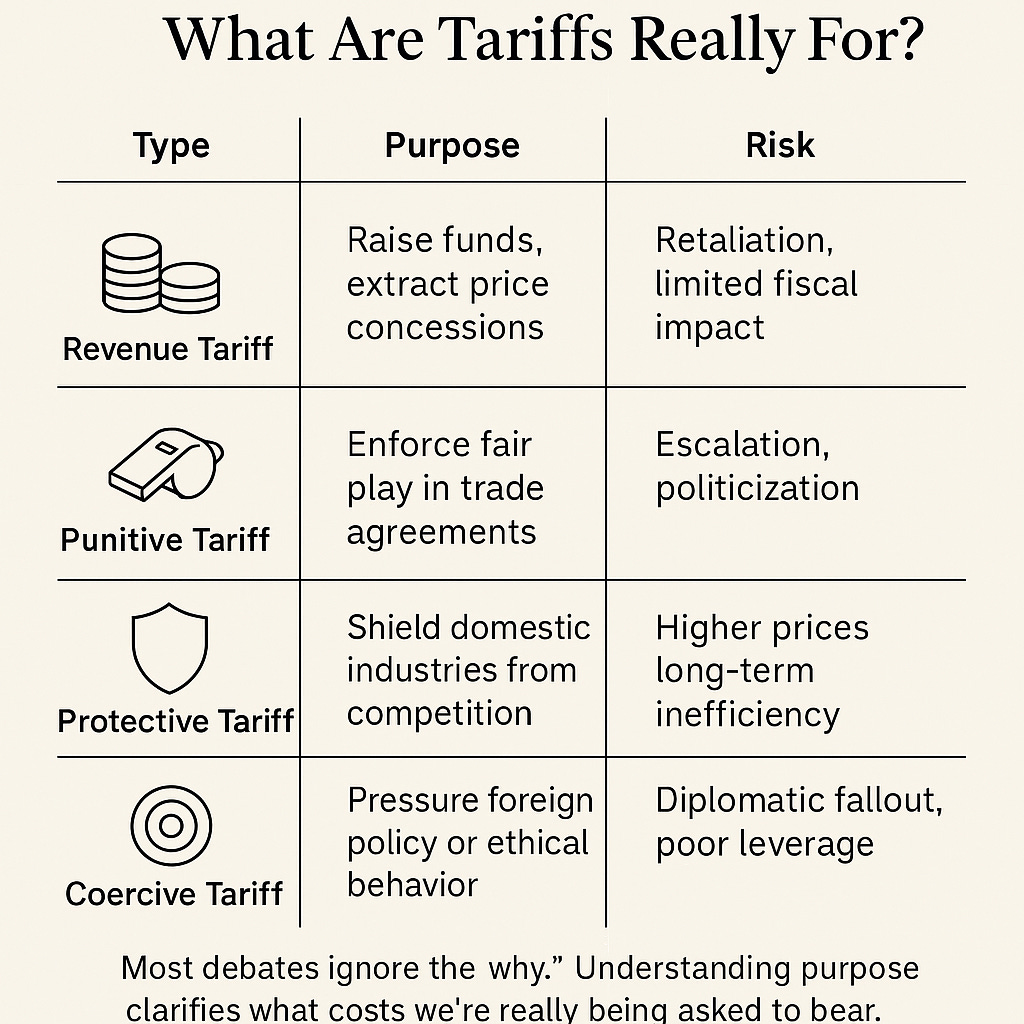

The Four Reasons for Tariffs

Governments don’t use tariffs randomly. Behind every one is a goal, sometimes well thought out, sometimes just political instinct. Broadly speaking, there are four main motivations. Each has its logic. Each has its limits.

1. Revenue Tariffs: Money, Money, Money

In the early days of nation-states, tariffs were a government’s primary source of revenue. Before income taxes or sales taxes were practical, taxing imports at the border paid for roads, armies, and bureaucracies. Some developing countries still use them this way.

In modern economics, there’s a more advanced version: the optimal tariff. This applies when a country is a disproportionately large buyer of a good, like the U.S. importing rare earth elements. If the country has enough market power, it can impose a tariff that pressures foreign producers to lower their prices just enough to keep their sales volume from dropping. The tariff raises revenue, and the import price stays roughly the same for domestic buyers.

That’s what makes it “optimal”: it shifts costs to the exporter without hurting the consumer, in theory. The trick is taxing just enough to extract a better deal without triggering retaliation or price hikes.

The limits? It only works if other countries tolerate it, and they usually don’t. Retaliation is the rule, not the exception. And even when it works, the gains are modest. Tariffs once funded navies. Today, they’re more like loose change in the couch cushions of a modern tax system.

2. Punitive Tariffs: The Baseball Bat

Punitive tariffs target bad actors in a trade system built on rules. These are countries that have signed on to free trade agreements but then violate the terms by dumping goods below cost, subsidizing exports, or manipulating origin labels. The goal isn’t just retaliation, it’s discipline. Tariffs are used to eliminate mercantilist behavior inside a supposedly rules-based system.

Think of it like sports: every team agrees to the same rules. If one starts cheating, the referee steps in. In trade, that referee is sometimes the WTO, but often it’s just another country applying pressure until the offender backs off.

The upside: they can restore fairness, deter future abuse, and give rule-following industries a chance to compete on level ground.

But enforcement gets messy. It’s often hard to distinguish between illegal dumping and legal competitiveness. Governments subsidize all kinds of things—energy, research, labor. Drawing a line between “cheating” and “industrial policy” gets political fast.

And of course, if the accused country doesn’t concede, things escalate. Tit-for-tat tariffs can spiral into a broader trade war, hurting both sides and destabilizing the system they’re meant to defend.

3. Protective Tariffs: Guarding the Home Front

This is the classic political justification: protect domestic industries from foreign competition. Whether it’s steel, semiconductors, or agriculture, the logic is that some sectors are too important or too fragile to leave exposed.

Supporters argue that tariffs preserve jobs, foster industrial capacity, and buy time for companies to become competitive. In some cases, like “infant industries” in developing countries, there’s a real case to be made.

The tradeoff? Protection reduces pressure to innovate. Shielded from competition, firms often stagnate. Consumers pay higher prices, and industries may become addicted to the support they were only supposed to need temporarily. Worse, if tariffs stay long after their rationale has expired, they can trap the economy in a low-efficiency equilibrium: jobs preserved on paper, but progress stalled.

Some protection may be justified, especially in national security or supply chain resilience. But permanent walls tend to block more than they save.

4. Coercive Tariffs: Trade as Leverage

These are tariffs meant to change behavior outside the world of trade, targeting countries for human rights violations, environmental abuse, or geopolitical aggression. Sanction tariffs on Russian oil, or environmental tariffs on carbon-heavy imports, fall into this category.

They’re not about economics. They’re about values and influence. If you want another country to act differently, making trade more painful is one way to apply pressure.

The risks are obvious: if the target doesn’t give in, both sides suffer economically with no real benefit. Worse, coercive tariffs can alienate allies, confuse supply chains, and shift power to players who don’t care about the values being enforced. Even when the goals are noble, the means can backfire.

Conclusion: Purpose First, Then Policy

Tariffs aren’t good or bad in themselves. They’re policy tools—blunt ones, often—meant to serve a purpose. Whether the goal is to raise revenue, punish bad behavior, protect key industries, or apply geopolitical pressure, the value of a tariff lies in what it’s trying to accomplish and whether the cost is worth the attempt.

These costs aren’t just academic. They show up in the form of higher prices, thinner margins, strained alliances, or preserved industries. They shape job markets and influence the resilience of supply chains. That’s why debates about tariffs so often feel like they’re talking past each other. Because they skip the foundational questions.

So the next time a tariff hits the news or a candidate promises to impose one, don’t start by asking whether it’s “isolationist” or “anti-free market.” Start by asking: What’s the goal? Do I agree with it? And does this policy actually stand a chance of achieving it without too much collateral damage?

That’s where the real conversation begins. And if more of us start asking those questions, maybe the next round of decisions will be made with a little more clarity and a lot less theater.

🔍 Addendum: Concepts, Connections, and Further Reading

✅ Key Concepts Covered

Tariffs as policy tools, not just taxes

Types of tariffs by motivation:

Revenue Tariffs (including Optimal Tariffs)

Punitive Tariffs (Retaliatory tariffs to enforce trade rules)

Protective Tariffs (Support for domestic industries or strategic sectors)

Coercive Tariffs (Sanctions or pressure for non-trade objectives)

Trade-offs and downstream effects of tariffs

Importance of understanding intent over surface-level categorization

🛠️ Related Topics

Terms of Trade

Strategic Trade Theory

Deadweight Loss and Market Distortions

Trade Agreements and WTO Rules

Mercantilism vs. Free Trade

Industrial Policy

Game Theory in Trade Disputes

Global Supply Chain Resilience

📚 Recommended Reading and Resources

Pop Internationalism – Paul Krugman

The Choice: A Fable of Free Trade and Protectionism – Russell Roberts

Straight Talk on Trade – Dani Rodrik

EconTalk podcast episodes on trade and tariffs